By Didem Uca

“Twitter as archive/twitter as sketchbook/as feedback loop/as void/as filesharing network/as an instrument of collaboration/as a megaphone/as therapy.” (Zarina Muhammad, https://www.artrabbit.com/events/live-broadcast-chat-show-with-zarina-muhammad)

Twitter, like other mainstream social media outlets, is an outlet for the virulent and often anonymous expression of misogyny, racism, and other violent forms of discrimination––even by the current U.S. President. Yet it is also where social justice issues are discussed in real time and where users can garner support for movements that have consequences beyond the web; to name just a few examples, the hashtags #BlackLivesMatter and #SayHerName have long brought attention to police brutality and other forms of violence towards Black Americans, while the Me Too movement, founded by civil rights activist Tarana Burke in 2006 and popularized through the spread of #MeToo on Twitter over a decade later, has helped to expose the pervasiveness of sexual harassment and assault for women. Twitter also serves as a means to combat the rampant misinformation of Trump’s administration and deal, sometimes through memes and GIFs, but often through careful collaborative analysis, with the trauma surrounding his tenure. But in what sense might we consider Twitter as not just an ephemeral, if ubiquitous, mode of communication and organizing, but, indeed, as feminist archive?

Twitter also serves as a means to combat the rampant misinformation of Trump’s administration and deal, sometimes through memes and GIFs, but often through careful collaborative analysis, with the trauma surrounding his tenure. But in what sense might we consider Twitter as not just an ephemeral, if ubiquitous, mode of communication and organizing, but, indeed, as feminist archive?

In An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (2003), Ann Cvetkovich writes about trauma from her perspective as a feminist, lesbian, and sexual assault survivor, positing that her intervention is less about understanding these forms of trauma through a main stream lens and more about considering “a sense of trauma as connected to the textures of everyday experience” (3–4). Perhaps the act of voicing our individual traumas on Twitter and finding others who share it might function like trauma theory did for Cvetkovich, which became a site that allowed her to “ask about the connection between girls like me feeling bad and world historical events” (3). During my five years managing the Coalition of Women in German’s Twitter account, @womeningerman, I have grown to see it as a form of feminist archival practice, sequencing an alternate “timeline” (to mix social media metaphors) in a time of widespread racism, misogyny, xenophobia, anti-LGBTQ sentiment, Islamophobic and antisemitic sentiments, and ableism.

The Coalition of Women in German is a feminist German Studies organization founded in 1974 by professors and graduate students who sought a venue for their scholarship, intellectual community, and mentorship in the male-dominated field of North American German Studies. WiG has been at the forefront of feminist scholar-activism for over forty years and continues to develop in increasingly intersectional and interdisciplinary directions. At a conference in Shawnee, Pennsylvania five years ago, members expressed interest in broadening the organization’s reach. At that time, it had nothing in terms of a public-facing social media profile that could share our activities and communicate our commitments. Therefore I volunteered to found and manage @womeningerman.

As interest in the account grew, it became clear that its reach would far exceed the organization’s membership of about 300. Currently, the account has over 1660 followers, which is a high number for an academic organization of a fairly specific scope. Our average number of impressions is about 30,000 per month, with some months far exceeding this (e.g. the conference month of October 2019 has made over 131,000 impressions and counting), while certain tweets, such as one announcing the latest volume of our journal, Feminist German Studies, has made over 61,000 impressions. The initial primary purpose of the account was to highlight the scholarship, teaching, and activism our members are doing on their campuses and in the profession through initiatives like #WiGgiesInAction. These additional clicks on articles and book projects can lead to greater reception and opportunities for collaboration, while featuring stories of members’ successes in the classroom create positive hits for Google search algorithms. Social media mentions raise scholars’ Altmetric scores, which may even serve to increase likelihood of tenure and promotion.

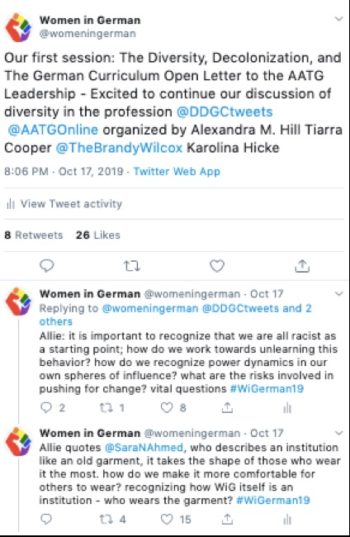

However, beyond the important goal of gaining a broader audience for our members’ work, the account itself serves as a platform for members to engage in conversations on social justice within the German-speaking and U.S. American contexts, both within and beyond academia. In this way, Twitter can become a vital force for scholar-activism. The account shares resources that center the experiences of people of color, queer folx, and women in German-speaking countries, retweets co-conspirators such as @Blackgermans and the newcomer @DDGCTweets, and initiates conversations through creating hashtags such as #GermanStudiesSoWhite. Promoting campaigns and events such as the #FeminismToMe Instagram-based exhibit at the Goethe-Institut in D.C., to which many of our members contributed, employs online resources to further feminist causes within more traditional cultural organizations, even impacting their physical spaces. The account also amplifies open letters written by colleagues to address the problematic actions of our professional organizations and attacks on the humanities and language learning. These online activities in turn shape our conferences and organizational commitments; for example, the strong response of our membership to the online Open Letter to the AATG: A Ten-Point Program of the Diversity, Decolonization, and the German Curriculum (DDGC) Collective, which several of our members helped draft and many more signed after it was shared to social media and email listservs, became our 2019 conference’s Thursday night coalitional feminism in action session, organized by Dr. Alexandra M. Hill and facilitated by Ph.D. candidates Tiarra Cooper, Karolina Hicke, and Brandy E. Wilcox. By then live-tweeting the discussion online, @womeningerman creates and archives a hybrid mode of virtual/visceral scholar-activism that is accessible and accountable to multiple audiences simultaneously.

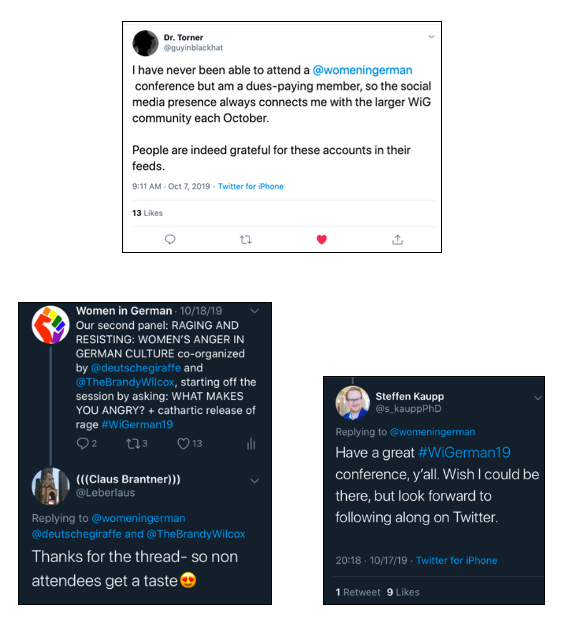

The account also amplifies open letters written by colleagues to address the problematic actions of our professional organizations and attacks on the humanities and language learning. These online activities in turn shape our conferences and organizational commitments; for example, the strong response of our membership to the online Open Letter to the AATG: A Ten-Point Program of the Diversity, Decolonization, and the German Curriculum (DDGC) Collective, which several of our members helped draft and many more signed after it was shared to social media and email listservs, became our 2019 conference’s Thursday night coalitional feminism in action session, organized by Dr. Alexandra M. Hill and facilitated by Ph.D. candidates Tiarra Cooper, Karolina Hicke, and Brandy E. Wilcox. By then live-tweeting the discussion online, @womeningerman creates and archives a hybrid mode of virtual/visceral scholar-activism that is accessible and accountable to multiple audiences simultaneously. Indeed, live-tweeting the annual conference has made it possible for people unable to attend to nevertheless join the conversation. As Dr. Evan Torner recently tweeted from his public account @guyinblackhat, “I have never been able to attend a @womeningerman conference but am a dues-paying member, so the social media presence always connects me with the larger WiG community each October. People are indeed grateful for these accounts in their feeds.” These sentiments are echoed by other non-attending members and supporters.

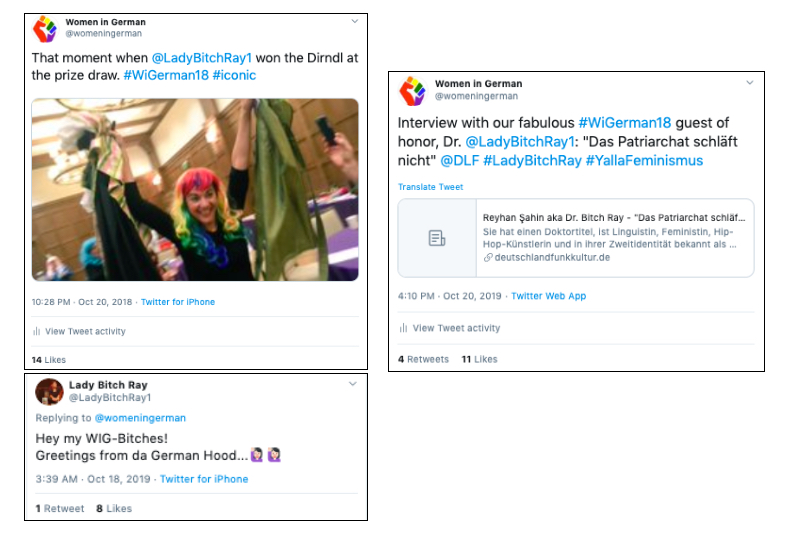

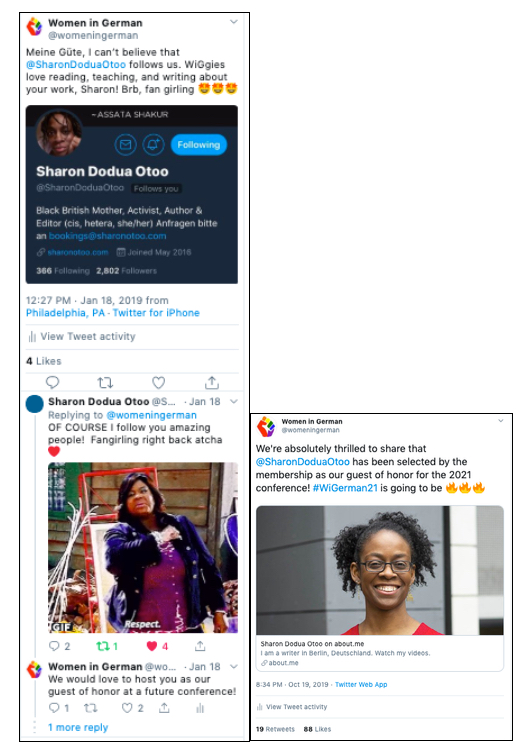

Indeed, live-tweeting the annual conference has made it possible for people unable to attend to nevertheless join the conversation. As Dr. Evan Torner recently tweeted from his public account @guyinblackhat, “I have never been able to attend a @womeningerman conference but am a dues-paying member, so the social media presence always connects me with the larger WiG community each October. People are indeed grateful for these accounts in their feeds.” These sentiments are echoed by other non-attending members and supporters. Furthermore, our social media presence has allowed us to engage with the work of leading feminist artists of color in the German-speaking world both on- and offline. Our 2018 guest of honor, Reyhan Şahin aka Dr. Bitch Ray, continues to engage with us on Twitter (@LadyBitchRay1), while the first Twitter-based correspondence with Sharon Dodua Otoo (@SharonDoduaOtoo) happened after realizing that she follows the account and then asking her to consider attending as our guest of honor in the future––a hope that will come to fruition in 2021.

Furthermore, our social media presence has allowed us to engage with the work of leading feminist artists of color in the German-speaking world both on- and offline. Our 2018 guest of honor, Reyhan Şahin aka Dr. Bitch Ray, continues to engage with us on Twitter (@LadyBitchRay1), while the first Twitter-based correspondence with Sharon Dodua Otoo (@SharonDoduaOtoo) happened after realizing that she follows the account and then asking her to consider attending as our guest of honor in the future––a hope that will come to fruition in 2021.

The routine exclusion of marginalized cultural producers from traditional archives is both due to and reinforces their exclusion from our canons, literary and cultural histories, and curricula. Through projects like @womeningerman, our activism in the archives can extend into the virtual sphere and back outward. The very existence of an active Twitter presence that highlights issues of marginalization and exclusion in German Studies can serve to promote inclusion. One follower, an Assistant Professor who asked to remain anonymous, recently direct messaged the account to share that it is “definitely something that makes German Studies relatable and inclusive. I honestly have never thought of myself as a Germanist until the past few years, because of how those in the academy viewed my research. It’s really been ONLY through Twitter and a couple presentations at ACTFL that I’ve felt welcomed into German Studies.” By cultivating our own audience and intervening in the whitewashing, mansplaining, and exclusionary tendencies of our field, @womeningerman indicates that social media can function not only as a conversation starter and way to stay tuned into the Zeitgeist, but also as an archive of our scholarship, our activism, and, yes, our #BadFeelings, which can thus transform into meaningful coalitional action.

The routine exclusion of marginalized cultural producers from traditional archives is both due to and reinforces their exclusion from our canons, literary and cultural histories, and curricula. Through projects like @womeningerman, our activism in the archives can extend into the virtual sphere and back outward. The very existence of an active Twitter presence that highlights issues of marginalization and exclusion in German Studies can serve to promote inclusion. One follower, an Assistant Professor who asked to remain anonymous, recently direct messaged the account to share that it is “definitely something that makes German Studies relatable and inclusive. I honestly have never thought of myself as a Germanist until the past few years, because of how those in the academy viewed my research. It’s really been ONLY through Twitter and a couple presentations at ACTFL that I’ve felt welcomed into German Studies.” By cultivating our own audience and intervening in the whitewashing, mansplaining, and exclusionary tendencies of our field, @womeningerman indicates that social media can function not only as a conversation starter and way to stay tuned into the Zeitgeist, but also as an archive of our scholarship, our activism, and, yes, our #BadFeelings, which can thus transform into meaningful coalitional action.